Family Burial Plots

Family internment plots in Prince George’s County were a result of need. For families living on confined estates or ranches during the province’s initial settlement in the eighteenth century, it was regularly unfeasible to move the dead to the closest town or churchyard; thusly, the expired were entombed on the grower’s property. At whatever point conceivable, family entombment plots were put on the edge of a field or at the most noteworthy purpose of the property. Few Headstones shows the history of the person. At first, little wooden markers were utilized to signify the graves. Afterward, tombstones cut from sandstone, marble, or rock supplanted the wooden markers. Regularly, the cemetery would be encircled by a wood fence or stone divider. Overhanging trees were frequently planted close by, what’s more, other fancy plantings made a nursery like setting. Family internments on ranches and homesteads stayed regular through the Civil War as the tobacco-based economy strengthened the scattered settlement design in the province; notwithstanding, church internments turned out to be more normal as networks assembled more places of love. After the Civil War, ranches were supplanted with more modest family cultivates. While interments proceeded on family cultivates into the 20th century, the training turned out to be more uncommon as the homesteads offered an approach to private networks.

Slave Cemeteries

Slave entombments are hard to distinguish as they infrequently contain indelible markers or fenced in areas. Tragically, a couple of slave burial grounds have been found in Prince George’s County. In any case, firsthand records from the nineteenth century and oral chronicles recommend that slave internments on manors happened with some routineness. It is known from the disclosure of slave graveyards in different districts that white growers frequently committed a little territory of their manors for slave entombments. Most manor slaves were covered inside these assigned zones; notwithstanding, trusted or deep-rooted workers may have been covered close to their lord’s family entombment plot. Slaves had little command over their customs of entombment. Graves in slave burial grounds were regularly plain, even though little wood or stone markers were periodically utilized. A significant number of the customs and conventions related to slave entombments have been lost, as have the areas of plain slave burial grounds.

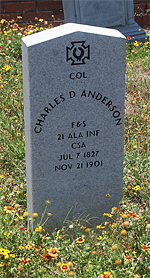

Christian Cemeteries

Numerous burial grounds in Prince George’s County are related to strict gatherings and their places of love. The early European pilgrims of the province were individuals from several Christian sections and were covered in chapel cemeteries solely saved for individual parishioners. Anglican, Protestant, and Catholic graveyards were regularly found straightforwardly nearby the congregation. This situation empowered parishioners to be covered close to the special raised area and represented the progression of the confidence. After some time, populace development in the area required territorial graveyards just as those appended to houses of worship. Even though taken out from their places of love, these bigger burial grounds stay a necessary piece of strict customs and rituals and are viewed as consecrated spaces. In many church graveyards, early graves were spread out in an arbitrary style, however, after some time, markers were all the more generally positioned in a direct game plan. Regularly, graves were too masterminded in little family plots inside chapel graveyards. Markers are ordinarily arranged along with an east/west hub—a training got from the conviction that upon Judgment Day, a body will emerge pointing toward the east fully expecting the Second Coming. In the nineteenth century, Christian graveyards started to mirror a more hopeful demeanor toward life following death and cheerfulness for the revival.